The popularity of Advent of Code cannot be understated. In it’s fifth year, the 2020 edition of Advent of Code had just over 1.3 million puzzle completions throughout the month of December. (source)

I found Day 20: Jurassic Jigsaw to be the most challenging puzzle this year. While the problem was not difficult to understand, the solution required so many steps that many opted out of the puzzle entirely. According to AoC completion statistics, day 20 was the second least completed puzzle of 2020 (behind the Christmas Day puzzle).

In this blog post, I’ll walk you through my solution to this puzzle.

If you want to jump straight into the code, you can find the entire solution on github.

Day 20 - Jurassic Jigsaw

The Problem

Our input consists of 144 tiles that need to be reassembled to form a single image (like a jigsaw puzzle). Here’s an example of two tiles from the sample data

Tile 1951: Tile 2311:

#.##...##. ..##.#..#.

#.####...# ##..#.....

.....#..## #...##..#.

#...###### ####.#...#

.##.#....# ##.##.###.

.###.##### ##...#.###

###.##.##. .#.#.#..##

.###....#. ..#....#..

..#.#..#.# ###...#.#.

#...##.#.. ..###..###

Tiles can be rotated and flipped until one of their sides match. In the above example, Tile 1951’s east edge matches Tile 2311’s west edge in their current orientation.

Once the image is reassembled, we are asked to count the frequency of sea monsters in image. This is a sea monster:

#

# ## ## ###

# # # # # #

Modeling The Problem

Since I like to solve AoC problems using Object Oriented Ruby, I begin each problem by identifying the key abstractions in the problem domain and modeling them with objects.

A Tile class seems like an obvious choice for this problem, so i’ll start there. I’ll store tile rows as an array of strings in the @rows instance variable.

class Tile

def initialize(id:,rows:)

@id = id

@rows = rows

end

end

I’ll also create an Image class to represent a set of Tile pieces.

class Image

def initialize(tiles:)

@tiles = Set.new(tiles)

end

end

After writing a few lines to code to read in the input file, we’re off to the races!

tiles = File.read("input.txt").split("\n\n").map do |data|

tile = data.split("\n")

Tile.new(id: tile.first.delete("^0-9"), data: tile[1..-1])

end

image = Image.new(tiles: tiles)

Now, let’s move onto to solving the first puzzle of the day.

Puzzle 1 - Finding Corner Pieces

The first puzzle asks us to identify the corner pieces and calculate the product of their ID’s.

While we could assemble the entire image to identify the corner pieces, there is a simpler solution. Corner tiles have the unique characteristic of sharing an edge with exactly two other tiles. Therefore, we can reduce the problem to identifying the four tiles that share exactly two edges with other tiles.

Since we’ll be comparing tile edges, I created a method on the Tile class that returns the edges of a tile. Because tiles can be flipped and rotated, the method returns all eight possible edge orientations.

class Tile

# other code omitted...

def all_edges

@all_edges ||= begin

# N E S W edges

edges = [ @rows.first, @rows.map{|r|r[-1]}.join,

@rows.last , @rows.map{|r|r[0]}.join ]

Set.new(edges+edges.map(&:reverse))

end

end

end

Then, I created helper methods that determine if tiles are neighbors.

class Tile

# other code omitted...

# set intersection of edges

def shared_edges(tile)

all_edges & tile.all_edges

end

# true if tile is a neighbor, false otherwise

def neighbor_of?(tile)

self != tile && !shared_edges(tile).empty?

end

end

Dropping into an irb console, I can confirm this works as expected on a simple Tile with two rows. When in irb, I like to represent rows with numbers instead of ‘#’ and ‘.’ because I think it’s easier to visualize. Since the Tile class is storing the rows as strings, I can use whatever representation I’d like.

➜ irb

3.0.0 :001 > tile1 = Tile.new(id: 1, rows: ["12","34"])

=> #<Tile:0x00007ff3dc82a208 @id=1, @rows=["12", "34"]>

3.0.0 :002 > tile2 = Tile.new(id: 2, rows: ["12","56"])

=> #<Tile:0x00007ff3dc1ed228 @id=2, @rows=["12", "56"]>

3.0.0 :003 > tile1.all_edges

=> #<Set: {"12", "24", "34", "13", "21", "42", "43", "31"}>

3.0.0 :004 > tile2.all_edges

=> #<Set: {"12", "26", "56", "15", "21", "62", "65", "51"}>

3.0.0 :005 > tile1.neighbor_of?(tile2)

=> true

Because all_edges returns all possible edge orientations, I don’t need to worry about flipping or rotating the tile when checking for neighbors. Tiles are neighbors if the the intersection of their edges is not empty.

These Tile methods give me a convenient way to identify neighbors for each tile.

class Image

# other code omitted...

# return an array of neighboring tiles

def neighbors_of(tile)

@tiles.filter_map { |t| t if tile.neighbor_of?(t) }

end

# return a hash of tiles to their neighbors (an adjacency list)

def neighbors

@neighbors ||= @tiles.map{|tile| [tile, neighbors_of(tile)]}.to_h

end

def corners

neighbors.select{|tile,neighbors| neighbors.length == 2 }.keys

end

end

I decided to store the results of the neighbor calculations in an adjacency list, which lets me easily identify corner tiles and calculate the solution to the first puzzle.

➜ irb

# tiles is an array of Tile objects parsed from a file

3.0.0 :001 > image = Image.new(:tiles=>tiles)

=> #<Image:0x00007ff3dd181db0 @tiles=#<Set:...>>

3.0.0 :002 > image.corners.map(&:id).reduce(:*)

=> 23497974998093

Puzzle 2 - Reassemble The Image

The second puzzle is where things get mind numbingly awful interesting!

This puzzle requires us to reassemble the tiles into an image, strip the borders from each tile and count the number of times a specific pattern occurs in the combined image. Oh, and the reassembled image may itself need to be flipped and rotated to find the pattern.

(╯°□°)╯︵ ┻━┻

LETS GET STARTED!

Flipping and Rotating Tiles

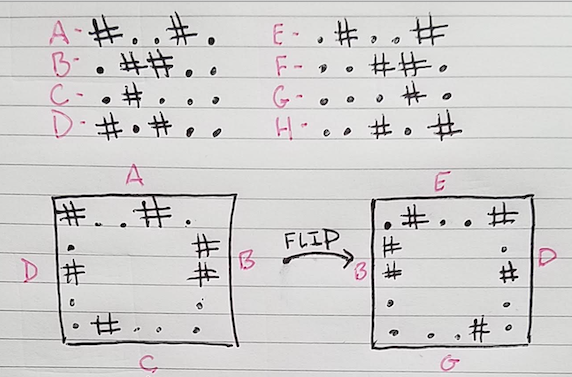

To make reasoning about this problem easier, I’ll assign labels to each of the eight possible tile edges. Starting from the north side of the tile and moving clockwise, I’ll use labels A,B,C and D and the reverse of these edges E,F,G and H.

For example, here’s the front and back of a 5x5 tile with edges labeled.

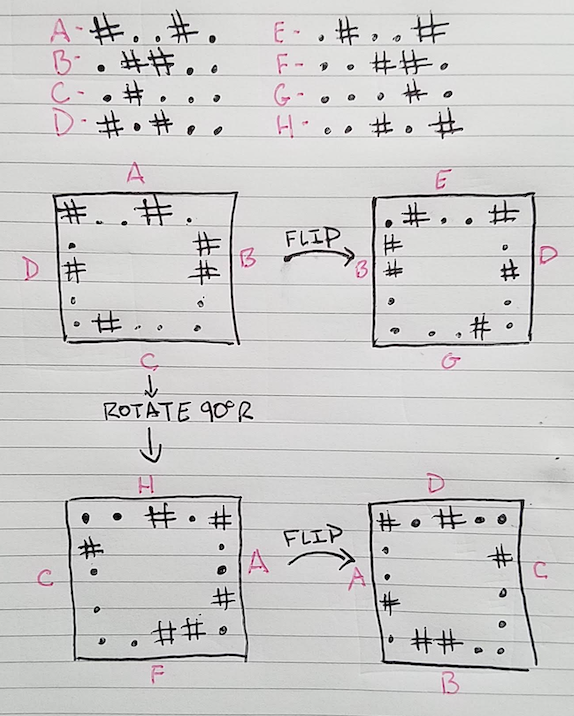

Using these labels, I can represent the front and back side of this tile as A,B,C,D,E,D,G,B. Note that edges F and H are not represented in this orientation, but will be if we rotate the tile 90 degrees to the right.

This newly rotated tile can be represented as H,A,F,C,D,C,B,A

Repeating this process two more times gives me a compact way to represent all possible tile orientations.

This concept translates nicely into Ruby, where I used arrays of symbols to represent the edges in each tile orientation.

class Tile

# other code omitted...

EDGE_LABELS = %i[a b c d e f g h]

EDGE_STATES = [%i[a b c d e d g b], # 0°

%i[h a f c d c b a], # rotate 90°

%i[g h e f c f a h], # rotate 180°

%i[b g d e f e h g]] # rotate 270°

# returns the edge for the given label

def edge_for(label)

# hash of label to edge {a: "#..#.",b: ".##..",...}

@edge_hash ||= EDGE_LABELS.zip(all_edges).to_h

@edge_hash[label]

end

end

The edge_for method maps the labels to the string representation of the tile edge.

The EDGE_STATE array represents the front and back edges of a tile at each rotation (0°,90°,180°,270°).

Representing tiles in this way means I can avoid complex 2D array transformations while reassembling tiles. I only need to keep track of how many times the tile has been flipped or rotated.

As a result of how the edge states are modeled, the flip! and rotate! methods are dead simple.

class Tile

SIDES = {:N=>0,:E=>1,:S=>2,:W=>3}

EDGE_LABELS = %i[a b c d e f g h]

EDGE_STATES = [%i[a b c d e d g b], # 0°

%i[h a f c d c b a], # 90°

%i[g h e f c f a h], # 180°

%i[b g d e f e h g]] # 270°

def initialize(id:,rows:)

# ...

@flipped,@num_rotations = false,0

end

def rotate!

@num_rotations = (@num_rotations+1) % NUM_SIDES

end

def flip!

@flipped = !@flipped

end

# returns the edge at the specified direction (N S E W),

def edge_at(direction)

edge_index = @flipped ? SIDES[direction] + NUM_SIDES : SIDES[direction]

edge_for(EDGE_STATES[@num_rotations][edge_index])

end

end

Let’s walk through an example of this in action.

➜ irb

3.0.0 :001 > tile = Tile.new(id: 1, rows: ["12","34"])

=> #<Tile:0x00007fe6ac8a6bb0 @id=1, @rows=["12", "34"], @flipped=false, @num_rotations=0>

3.0.0 :002 > tile.edge_at(:N)

=> "12"

3.0.0 :003 > tile.flip!

=> true

3.0.0 :004 > tile.edge_at(:N)

=> "21"

3.0.0 :005 > tile.rotate!

=> 1

3.0.0 :006 > tile.edge_at(:N)

=> "13"

3.0.0 :007 > tile

=> #<Tile:0x00007fe6ac8a6bb0 @id=1, @rows=["12", "34"], @flipped=true, @num_rotations=1>

Arranging The Tiles

My solution to the first puzzle left me with an adjacency list, which means I already know the neighbors for each tile. To reassemble the image, I just need to flip/rotate each tile until it fits with it’s neighbors. Returning to the Tile class, I create an arrange! method that flips/rotates the tile until the edge is facing the requested direction.

class Tile

# other code omitted...

def arrange!(dir,edge)

return false unless has_edge?(edge)

8.times do |i|

return true if edge_at(dir) == edge

i == NUM_SIDES-1 ? flip! : rotate!

end

end

end

To reassemble the image, I start by selecting and placing a corner tile in the upper left of the image. Next, I perform a breadth first traversal of the adjacency list, rotating/flipping and placing neighboring tiles as I go. This process continues until the traversal is complete.

class Image

def initialize(tiles:)

@tiles = Set.new(tiles)

@dimension = Math.sqrt(tiles.size)

@image = Array.new(@dimension){Array.new(@dimension)}

end

# other code omitted...

def reassemble!

corner = corners.first

# rotate corner into position

se1,se2 = neighbors[corner].map{|tile| corner.shared_edges(tile) }

8.times do |i|

break if se1.include?(corner.edge_at(:E)) && se2.include?(corner.edge_at(:S))

i == 3 ? corner.flip! : corner.rotate!

end

# place the corner tile

place_tile(tile:corner,row:0,col:0)

# process the rest

assemble_image!(tile: corner, row:0, col:0)

end

def assemble_image!(tile:,row:,col:)

return if row >= @dimension || col >= @dimension

neighbors[tile].each do |t|

unless @seen.include?(t)

if t.has_edge?(tile.edge_at(:E))

t.arrange!(:W, tile.edge_at(:E))

place_tile(tile:t, row:row, col:col+1)

assemble_image!(tile:t, row:row, col:col+1)

elsif t.has_edge?(tile.edge_at(:S))

t.arrange!(:N, tile.edge_at(:S))

place_tile(tile:t, row:row+1, col:col)

assemble_image!(tile:t, row:row+1, col:col)

end

end

end

end

def place_tile(tile:,row:,col:)

@seen ||= Set.new()

@seen.add(tile)

@image[row][col]=tile

end

end

Assembling The Image

The last step in reassembling the image requires us to strip the borders from each tile.

class Tile

# other code omitted...

def remove_borders

rows.dup[1..-2].map{|row|row.slice!(1..-2)}

end

end

Before we merge the tiles together, recall that my solution has only involved tile edges. I’ve never once changed the orientation of the tile rows at any point. Before reassembling the tiles into a larger image, it’s time to apply the rotations and flips to all rows of the tile. I wrote a method on the Tile class called refresh, which returns a copy of the tile rows with the flip/rotate transformations applied.

class Tile

# other code omitted ...

def refresh

rows = @rows.dup.map{ |row| row.split("") }

@num_rotations.times { rows = rows.transpose.map(&:reverse) }

rows.map(&:reverse!) if @flipped

rows.map(&:join)

end

end

The Tile class never modifies the tile rows directly. I found the problem easier to reason about if the tile rows were separate from it’s orientation. This just-in-time tile flipping and rotating prevents my code from unnecessarily transforming 2D arrays at every step of the process. It also made debugging much simpler.

For good measure, I also added a rows method that calls refresh on the tile and caches the result for the given flip status and number of orientations. This ensures that tile transformations are never repeated.

def rows

@rows_cache ||= Hash.new {|h,k| h[k] = refresh }

@rows_cache[[@flipped,@num_rotations]]

end

You can see the caching in action in irb

➜ irb

3.0.0 :001 > tile = Tile.new(id: 1, rows: ["12","34"])

=> #<Tile:0x00007fc734984150 @id=1, @rows=["12", "34"], @flipped=false, @num_rotations=0>

3.0.0 :002 > tile.rows

=> ["12", "34"]

3.0.0 :003 > tile

=> #<Tile:0x00007fc734984150 @id=1, @rows=["12", "34"], @flipped=false, @num_rotations=0, @rows_cache={[false, 0]=>["12", "34"]}>

3.0.0 :004 > tile.rotate!

=> 1

3.0.0 :006 > tile.rows

=> ["31", "42"]

3.0.0 :005 > tile

=> #<Tile:0x00007fc734984150 @id=1, @rows=["12", "34"], @flipped=false, @num_rotations=1, @rows_cache={[false, 0]=>["12", "34"], [false, 1]=>["31", "42"]}>

Finding Sea Monsters

While this problem could probably be solved with a regex, I opted for a different solution (read: I suck at regexes).

I converted the sea monster into a set of (x,y) coordinates. Using those coordinates, I traversed my reassembled image checking the collection of points and counting when a match was found.

I put all this logic in a TileScanner class because my Tile class was starting to feel busy, and this seemed like a separate concern. The class operates on Tile objects; one for the reassembled image and one for the monster. Because it was smaller, I opted to flip/rotate the monster tile instead of the larger image.

You can check out the implementation here if you’re interested in the details.

Conclusion

We made it! Phew, that was…a lot.

Day 20 took a ton of effort. While the problem was simple to understand, the implementation required significantly more code than any other puzzle this year. This was the only Advent of Code puzzle I did not complete the day it was released. However, I had much more fun solving the problem after I had a chance to think more deeply about the solution.

The entire solution, along with unit tests and sample input can be found on github.

Comments